Wednesday was one of those “it’s warm and dry, better do some work outside” days on the homestead. My wife handled the garden while I took care of the bees and the firewood.

It was in the mid-fifties, which was a welcome break after days in the 30s and nights in the 20s. The warm weather and sunshine meant the bees were flying for the first time in several weeks.

On warm winter days, the bees that leave their hive do not fly long distances looking for pollen or nectar. Instead, they take “cleansing flights.” That’s a polite way of saying they leave the hives for a bathroom break. Since bees won’t poop in their hives, the cleansing flights are a necessity and promote good bee health. In very cold climates, when they may be in the hive for months, the bees first cleansing flight can stain the snow and surrounding area brown.

I took advantage of the warm weather and high bee mobility to feed them bees a batch of two-to-one syrup. I put five pounds of water in a big pot and heated it up, gradually stirring in the contents of a 10-pound bag of sugar. That gave me enough syrup to give each of the six hives about a quart of syrup. I don’t want to overdo the feeding because we expect colder weather in a few days and the bees don’t process the syrup well when temperatures fall.

Last year we had some warm days around Christmas and I fed them then as well. So far, this winter has been colder than last, so we’ll have to see if I have another opportunity.

Bee Hive Insulation

Animals have many ways to survive over long winters. Many hibernate, slowing their systems down. Some shelter in holes or bury into the mud. Many insects die, leaving eggs to be hatched next year. Contrary to what many assume, bees do not hibernate. They form a cluster in the center of their hive and use their muscle power to generate heat. This heat is used to keep the queen warm and to keep any brood warm, which means they can have fresh bees hatching in the spring. Bees in the cluster rotate their positions so no bee is on the outside of the cluster, where it is coldest, for too long.

How large the cluster is depends on how healthy the hive is and how many fat-bodied bees were born in time for the winter. All but one of my hives had a large amount of bees in them when I last checked in the beginning of the month. I believe they are in better shape than they were going into last winter.

Since heat rises, I decided to help my bees out.

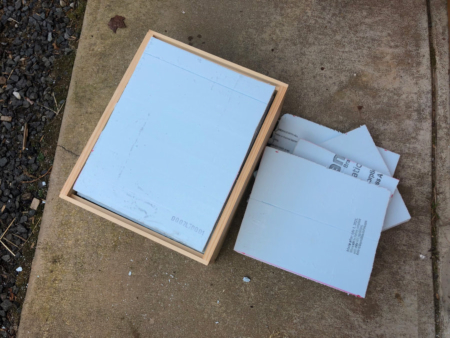

Earlier in the week, I picked up a 4’ x 8’ sheet of blue Styrofoam insulation meant for the building trades. The local lumber yard only had the 1-inch thick foam, but carries a 5R rating. I cut this large sheet into six rows of 14.5” x 4’ and then cut two 18” pieces out of each row. This gave me 12 pieces of foam 14.5” x 18”, just enough to put two pieces inside a shallow or medium super on top of each hive. (The inside of a 10-frame hive is 14.75” x 18.25” but I found I had to aim a tad smaller to get the foam to easily slide in and out of a box.)

Tar Paper Wrapping

I also wrapped my hives in tar paper. This does not provide much insulation, but it helps cut wind, and we get lots of wind. It also helps the hives heat up on sunny days. Beehives are traditionally white so they don’t over heat in the summer, but that doesn’t help them in the winter. The tar paper I staple to the hives absorbs the sun’s heat and transmits it to the cold wooden hive even when it is cold outside.

Bees have a long history of surviving the winter in the hollow trees and other natural hives they create in the winter. My tar paper and insulation is just to increase the odds of their survival. Even if it increases the average temperature in the hive by only 5 degrees over the months of December through march, that could be the difference between bees living and dying. It should also cut down on condensation, which can happen when the warm air inside the hive hits the cold exterior hive wall.

In northern locations, people build a foam box and insulate the entire hive. I doubt I will take this approach. Professional beekeepers don’t insulate their hives, but that’s because they have too many. I think the roof insulation, however, is a good compromise.

Buying new bees costs anywhere from $180 to $225 per hive. I spent less than $5 to insulate each hive. Considering the investment I’ve made in bees, that’s a cost I can live with.

I hope my bee yard has reached the size where I can produce all my own bees and no longer need to buy new ones. How well they survive this winter will be the true test.

Farm Yard Inflation

Like the cost of just about everything else, it’s becoming increasingly expensive to be a beekeeper. In May 2022, I bought five unassembled commercial hive bodies for $20.85 each. Today, they are $26.50. That’s a 27 percent price jump in six months. In April 2021, the same item was 16.90. The cost of an unassembled beehive has grown by 59 percent in about 18 months. Ouch!

Two years ago, I looked into the price of buying lumber and building my own hives. I determined I could buy unassembled hives more cheaply than I could buy lumber and cut my own hives. Now I have to recalculate. I am already building boards and lids to save money, but the rising costs will limit how quickly I can expand my bee yard. Each colony uses two hive bodies, a bottom board and a top board.

While we are discussing costs, let me also mention that our egg production is cut in half. My chickens are laying only six eggs per day because some of them are molting and the days are growing shorter. That’s enough eggs for us to eat and maybe sell an occasional dozen, but we are not recouping our expenses like we did this summer. As a result, all the math I did figuring my breakeven will have to be reworked.

Last winter, the chickens remained productive all winter because they were born in June and didn’t start producing eggs until October. I’ve decided to add eight new chickens each spring and cull the least productive. That should give me fresh chickens every year to keep egg production up through the winter.

Baby chicks are much cheaper than bees. Food and time are the big investments once you’ve built your coop.

The rising costs faced by farmers are one reason food prices are rising.

More Firewood, Please

We let both the woodstove and the fireplace insert burn out today. That gave me a chance to clean out the ashes. I also took advantage of the warm weather to restock our indoor woodpiles, something I have to do twice a week.

I estimate we have burned about 100 cubic feet of wood since our first fire of the season. That’s about $200 to $225 worth at the prices I paid, although replenish the stack might be more expensive. The good news is it looks like we’ll have more than enough to get us through the winter.

Happy Thanksgiving

Wherever and with whomever you are spending Thanksgiving, we wish you the very best of holidays.