I started working on my farmer tan this week. Not on purpose, but because it was finally warm enough to spend the day outside in a short-sleeve shirt. Coincidentally, I’d gotten a haircut earlier in the week, so I in addition to having pink arms I am officially a redneck.

Is spring here to stay? Of course not, but God graced us with a day we would not normally see until late May or June, so I will not complain. Sure, I’ll need to light the fire in the wood stove again this weekend, but for now, it was a day to work outside. So I spent seven hours doing just that.

I also received my first bee sting of the year. One bee crawled inside my glove and stung me on the back of my hand. Another stung me through the glove. That one doesn’t hurt, but my hand swelled up from the first sting, and I expect it will pulse once I go to bed. The first stings of the year always seem to be the worst. Oh well, at least I got it over with.

Checking for a Queen Cell

If you recall, I had a deadout after the sudden cold snap, so I removed all the dead bees, broke to hive down to a single hive body and repopulated it with brood and resources donated from two other hives. This new hive should create its own queen.

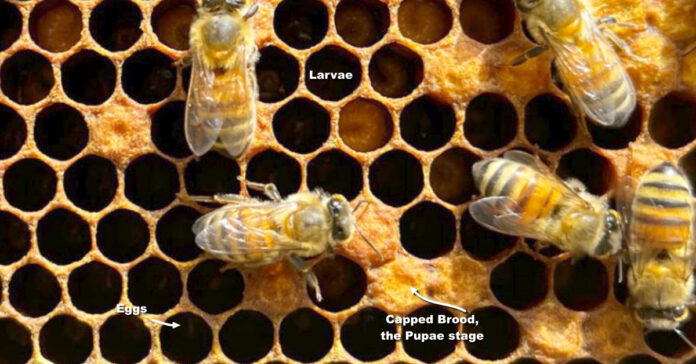

I inspected it ten days after creating it because this should have been enough time to create a queen cup and fill it. I expected to find multiple queen cells. Instead, there is brood. Young brood. I took a picture of the brood, and when I blew up the image on my phone, I could see eggs in the cells. (See the main image.)

This is a surprise. It means the hive has a queen, but it is way too early to have produced its own queen. Apparently, I moved the queen from one of the donor hives to the split and didn’t know it. That’s not terrible, but it wasn’t intentional.

This small hive didn’t have much in terms of resources, so I fed them half a pollen patty and some one-to-one sugar syrup to encourage them to grow. When I check again in another two weeks, they should be stronger and may be ready for a super or a second box.

Examining the Donor Hives

I opened one of the donor hives, and it is chock full of bees with plenty of fresh brood, so the queen didn’t come from that hive. Despite taking some resources ten days ago, this hive was busting at the seams. I decided to split it, but more on that later.

As I approached the other donor hive, I could hear the bees buzzing. This hive was LOUD. I have seen reports on YouTube stating queenless hives make more noise than queen-right hives, but that was the first time I had experienced it myself. This hive only had capped brood, meaning the have had produced no new eggs in the past ten days. That just confirmed that this was the queenless hive. This is also the hive that stung me. They were cranky.

I dug through this hive but did not see any queen cups. They hadn’t made a new queen, possibly because I had taken the young brood and moved it over to the split. I opened the hive next to it and found two nice frames of very young brood. I moved them to the queenless hive which should allow them to make a new queen from some day-old eggs.

This isn’t the first time a queen hasn’t been where I expected her. This is what happens when you aren’t very good at finding queens. I had looked at the frames I moved, but I hadn’t searched diligently enough. It’s also a good example of why you should check your hives ten days or so after you create a split or queenless hive. You might have gotten it wrong, as I did. This is one of those mistakes that is repairable when caught early. Had I waited three weeks, the hive would have been in bad shape and the bees might even have absconded.

Why you Should Split Bees

When left to their own devices, a colony of bees that outgrows its hive will swarm. A swarm is when the queen and between 30 and 70 percent of the bees leave the hive and look for a new home. In the old hive, queen cells hatch and the new queens battle it out with the strongest surviving to take over the hive. This swarming mechanism is how a bee colony reproduces to create new colonies.

When a hive swarms, the beekeeper loses half the bees from that hive and will make less honey. While beekeepers can sometimes capture swarms and put them in a new hive, they may also fly off and die or become feral bees. Feral bees don’t live very long these days because of the high mite population. In 25 to 30 percent of the cases, the newly hatched queen never returns from her mating flight, leaving the old hive to die. So swarming is best avoided.

Careful beekeepers manage their hives to prevent swarming. When done right, beekeepers keep their existing hive and end up with one or more new colonies of bees at no cost. That’s what I call a win-win.

Since the hive was brimming over with bees, I determined I should split it into two colonies. Doign so, I gave the queen more room to grow and reduced her headcount which will reduce the pressure on the hive to swarm.

The Doolittle or Overnight Split

Since I am obviously not the best at finding the queen, I used a splitting method that does not require finding the queen. I placed a new hive body nearby and put five empty frames in it. Then I sorted through the 20 different frames in the current hive and picked out the five I wanted to move, three of which had brood, some of it quite young. Then I shook the bees off these frames and put the now bee-less frames in the new hive body. Since there are frames with no bees, the queen is not on these five frames.

I then put the original hive back together, replacing the frames I took with two drawn frames and three frames with just foundation. This will give the old queen more space in which to lay and should make her feel less cramped, reducing the urge to swarm. On top of the old hive, I added a queen excluder and placed the new box, which is called the Doolittle box, on top of it and added an inside cover, a feeder, and the outer cover.

When the bees sense the brood in the top box, many of the nurse bees I shook off will return to the brood and start feeding the wet brood. As temperatures fall in the evening, more bees will migrate upwards to keep the brood warm. But the queen can’t get up there because of the excluder.

The Next Day

On day two, which is why this is sometimes called the overnight split, I removed the top box and set it up as a separate hive. The bees inside will come to accept it as their home. If all goes well, the bees will realize they have no queen and will work to turn one of those eggs I gave them into a replacement queen. I’ll check in a week or ten days and see if there are any queen cells.

You can see full instructions for making an overnight split at the Honey Bee Suite, an excellent beekeeping blog.