When you first move out of the city, you may find you have a septic system and a well instead of being on a municipal water and sewage system. That can be a surprise the first time the water stops working because of a power outage. It can be even more trouble if your septic fails and starts backing up. Since sewage relates to food, water and shelter, let’s address what preppers (or anyone else moving to the country) need to know about septic systems.

Note, the following content is intended for laypeople. It is not a detailed scientific explanation, but I hope it will give you a general idea of what is going on in your septic system, what can go wrong, and what you can do to keep it operating smoothly now and after the SHTF.

Why we Need Septic Systems

We all know that human feces can spread germs and disease, and the less we handle them, the better. We also don’t want our waste to reach the bodies of water we (or someone downstream) use as a water source for drinking, to water livestock, or even to irrigate a garden or farmland. Frankly, the world is sh*tty enough without us spreading more poop around.

A smoothly functioning septic system keeps both human waste and household wastewater underground, safe from run-off and away from surface water. Assuming the system is in good operating condition, waste is stored, digested by bacteria, and then safely disposed of, so any potential pathogens are absorbed or bonded to the soil or rendered inert by soil organisms.

Septic systems are a handy, turnkey sewage processing system used by 25 percent of the country’s population. Trat yours right and it will last for decades.

What is a Septic System?

In your traditional municipal sewer system, the waste water from every home flows down pipes to a central sewer pipe which is likely under or adjacent to the road. The combined waste from the neighborhood either flows via gravity or is pumped through more and larger pipes until it reaches the municipal wastewater or sewage treatment plant where it is treated it and clean water is release back into a river or other water system.

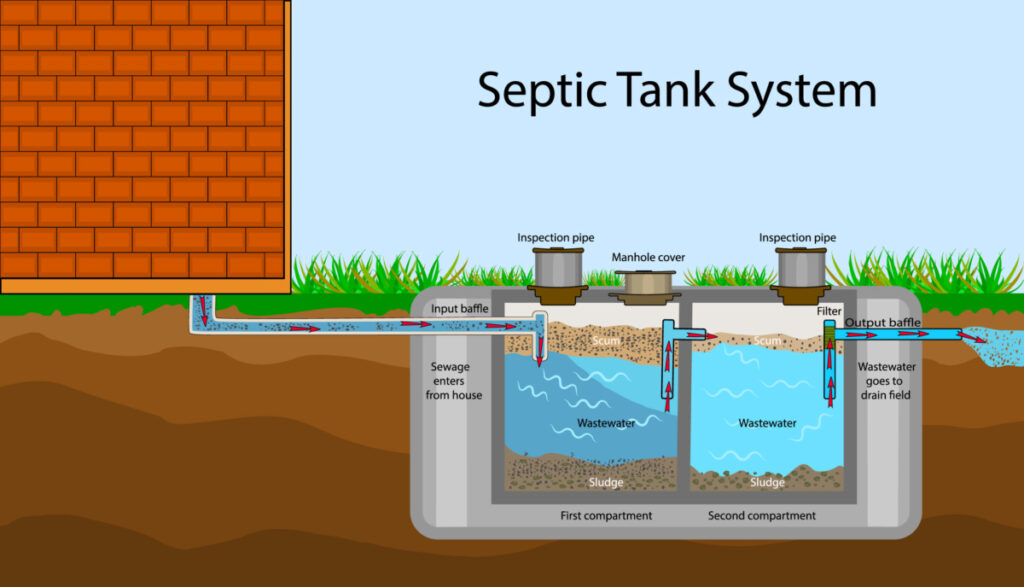

In a septic system, all your waste water flows from your house and into an underground tank. The average septic tank has a working capacity of 1,000 gallons, but if you were to fill it all the way to the brim, it would hold 1,200 gallons. Older tanks were made from concrete, but newer tanks are plastic. Plastic tanks are obviously lighter, cheaper and easier to install. The tank is where the solids are separated from the liquids. We’ll go into more detail on that below.

From the tank, wastewater—not the solids—flow to the leach field, which can also be called a septic field or just a drain field. The leach field consists of a distribution box that allows the wastewater to flow into three or more pipes, which are about 2 feet below ground. These pipes are perforated at the bottom and let the water seep or leach out of the pipe and percolate into the surrounding gravel and dirt. The water is absorbed by the dirt and any residual bacteria or chemicals are no longer available to contaminate you, your kids, your pets or livestock, or your pond and streams.

How a Septic Tank Works

Most tanks are divided into two sections. The waste water runs into section one, which is the bigger section. Several things happen here: Most solids float to the top. Some solids form a sludge on the bottom. There is a layer of brown water, known as effluent, in between. In the tank, helpful anaerobic bacteria digest the solids, including your poop and your toilet paper. Things like grease, fat, some food wastes, wipes, and condoms are not digestible. Try to keep them out of your tank.

The smaller section of the tank is separated by a baffle with a hole or holes in it. Ideally, only liquids pass from one side to the other, leaving the solids in section one. However, there may be some additional settling in this section. Once the tank is full, when waste water from the house enters the tank, any solids stay in compartment one and the liquid goes into section two. From there, it drains out of a pipe and runs into the leach field.

Gravity Fed

If you are lucky enough to have the septic tank and the leach field below the grade of your house, your septic system can be gravity fed and requires no electricity. That is ideal for a grid-down scenario because it means you can continue to use your toilet and sinks without worrying about the system backing up and spilling sewage into your house.

If your field is uphill from your tank or you have a specialized system, you will need a pump to force the effluent from a storage tank uphill to the septic field. In our system, the effluent flows from the second section of the septic tank into a holding tank. When the holding tank has 800 gallons in it, a pump kicks on and it pumps 600 gallons up to the leach field. Obviously, the less water we use, the less often the pump runs and the more recovery time the leach field has between uses.

This pump requires 240 volts, which my generator can produce. In the future, our solar system will power it in a grid-down scenario.

Septic System Size

Septic tanks are generally the same size for most houses. It’s the drain field that must grow to accommodate more people. Because municipalities and the health departments that give permits for septic installation assume the number of bedrooms in a house correlates to the number of people living there, a four-bedroom house will require a larger a leach field than a three-bedroom house, even if they both have four bathrooms.

As a prepper, this becomes pertinent if you double up during a disaster or bring more people into the home than the septic system is designed to handle. If you have twelve people living in a home with a septic system designed for four to six, you should not notice an immediate problem, but it will raise its ugly (and potentially smelly) head down the road.

When your septic field is overloaded, one of several things can happen. First, you might get water on the surface of your leach field because you are releasing more effluent than the system was designed to handle. Second, the holes in the pipe of the leach field could get clogged. To make a repair, the distribution box must be uncovered, hooked up some equipment and large gouts of air are blown through the pipe in hopes the air pressure will blast open the clogged holes. (Don’t count on this being done in a grid-down post-SHTF scenario.) Third, your septic tank might become overloaded with solids and clog up. (This is one potential cause of a backup into your home.) Normally, this can be addressed by pumping out the tank every three to five years, something unlikely to happen in a post-apocalyptic scenario.

Minimizing the Septic Burden

If you have ten people visit over the weekend, your septic system will handle it fine. If they stay for months, you are probably overloading and stressing your septic system. In that case, the best thing to do is to reduce the amount of water you send into it. The easiest way to do that is to dispose of your gray water outside the septic so it never reaches your leach field.

What is gray water? or our purposes, let’s consider it wastewater without poop in it. The water that goes down the drain when you shower or wash clothes, for example, is gray water.

I’m not suggesting that you violate any laws or codes, but in a survival situation, I would set up an outdoor shower and re-route my washing machine drain if I was worried about overloading my septic. I would also dig a slit or trench latrine and tell people to pee outside on all but the coldest or rainiest of days.

To take this a step further, you could also disconnect your sinks and put a bucket under there and then empty the bucket instead of letting the water from washing your face, brushing your teeth and cleaning your vegetables end up in the septic system. Or, you can set up an outdoor sink where the water just runs off. If you’re cooking outside over a fire, why not have the sink there, too?

Things to Avoid

When you live in a home with a septic system, there are a number of things you should not do now and after the SHTF:

- Don’t pour grease down the drain. Not only will your septic system have trouble digesting it, you could clog up your pipes and components.

- You should not have a garbage disposal, and if you have one, don’t use it. Throw out or compost the stuff you would usually grind up.

- Do not flush wipes, even if the box says they are flushable. They might go through the pipes, but they will form a solid mass at the top because of your tank and plug it up because they do not break down. (Municipal sewer systems hate wipes too.)

- Do not flush tampons, pads, paper towels, cotton balls, cigarette buts, Q-tips, or anything else thicker and heavier than toilet paper.

- Don’t flush your used condoms. They do not degrade and could clog up your system.

- Minimize the use of bleach or cleaning solutions with bleach in anything that drains into the septic. It will kill the beneficial bacteria that help digest all your solids.

- Don’t build a building, park a car, or let trees grow over your septic field as this can compress the dirt and make it difficult for the water to percolate through it. It also makes servicing the field far more expensive.

Things to Do

- Do use thin, cheap toilet paper. Seriously, you are better off using twice as much thin TP from a 1,000-foot roll of Scotts than to use the thick, quilted stuff. The less foreign objects in your septic tank, the better.

- Add specialty septic bacteria and/or enzymes to your tank a couple of time a year. Some say this won’t help or is unnecessary, but if the bacteria in your tank has been killed off by bleach, then you need may need to add more. I have a big bucket and when I remember, I add a scoop once a month. If you don’t have an official additive, I’ve heard you can add yeast. I’ve never done it myself.

- During the pre-SHTF times, get your septic tank pumped out at least once every five years, more often if you have a crowded house. If you have never had yours pumped, I recommend it as pumping removes both the slide and the floating solids. (You should also have it pumped and inspected prior to moving in.) Your pumper crew can tell you if your tank is in good condition and how many solids have built up. You can use that info to decide if you need to pump more frequently or less often in the future.

- If you can smell your septic system, that’s a sign something is going wrong and you need maintenance. A septic system that is working normally should be odor-free and the surface around it should be dy.

Can you Clean Your Own Septic Tank?

You should not try to clean or pump your own septic tank, but in a post-SHTF scenario, you may not be able to access a pumper truck. That means your system will eventually stop working, even if it takes decades.

If you’ve read Patriots, you may remember that they had to stop using their toilets except in an emergency because the additional people living in the house overloaded the septic system. While I would not recommend pumping your own tank, in a long-term emergency, you could try one of the following:

Dig a large hole, about the size of your septic tank. Then open your tank and use shovels, pitch forks, rakes and other implements to pull out as many of the solids floating on the top of your tank as possible. Also try to scoop them up form the bottom. (Don’t expect this to be easy or fun.) Throw all the solids into the new hole you dug. Then cover it up, burying it deep.

Alternately, if you have to have a junk pump, some gasoline to run it, and a 3-inch rigid hose, I guess you could pump the tank yourself and transfer the solids and liquid into the newly dug hole. Again, I don’t recommend this and I don’t think I’d want to try it. Whatever you do, keep the solids, effluent, and other tank contents out of any waterways and far from people and animals. And once you clean out the tank, try to minimize its use so you don’t have to repeat the experience of manually cleaning out your septic tank.

And while this should go with out saying, be sure to clean yourself using antibacterial soap after messing with your tank.

Cost Savings

When we got our tank pumped out, it cost $400, and that included digging the hole to access the lids. If we do this every five years, it works out to a cost of $6.67 per month. Pretty cheap, considering the average sewer bill is $63 a month. As long as our system continues to work, that is our only expense. So follow the above rules, and you’ll find your septic will save you money, too.

Video of the Day

This vides shows what can happen to a tank that has not been cleaned for 20 years. James Butler has lots of interesting content on YouTube, not just about septic tanks. But watch a few of his septic videos and you’ll be convinced cleaning your tank regularly will save you money in the long run. You’ll also never buy a house without first getting a septic inspection.