Two weeks ago, the temperature in the basement dropped to 65, so I lit a fire in the wood stove. By the time I went to bed, it had warmed up to 71°F. On Tuesday, my wife turned on the air conditioner because it was 76 degrees and humid upstairs. I guess we have a narrow comfort band.

In any case, it’s time to take the thick down comforter off the bed and switch out the flannel sheets.

Rain Turns to Sun

After seven inches of rain over six days and below-normal temperatures, we are enjoying a stint of sunshine. It took two days for the mud to dry up, and now we can walk in the chicken yard without going squish-squish. But that may not last as more rain is predicted late this week. It appears to be the typical summer pattern where we get a storm in the late afternoon or evening, rather than the long periods of rain interspersed with a few hours of sun we saw last week.

Down in the valley, the farmers are cutting hay. They are racing against the clock for it to dry and get bailed or rolled up before the next rain. I am down to one bail of straw myself, but will hold off until the last minute so I can buy new straw rather than last year’s.

The dog, who is not a big fan of rain and dislikes thunder, is happy with our current weather. Each time we walk her, she dives to the ground and rolls on the grass, flopping back and forth several times. Sometimes she jumps up afterwards and tears about; other times, she lies there enjoying the sunshine and refuses to finish her walk until her batteries are recharged. Who knew I had a solar-powered dog?

Unusual Weather Pattern

This was a cold winter. It included the longest period of below freezing temperatures we have experienced since moving here. It also had the most days of snow on the ground. There were weeks when we could leave the house only one day because of the snow on our road.

Then we had an early and surprisingly warm spring, followed by a cool, wet May. But we didn’t have frost at our elevation during May (sometimes there is frost in the valleys and we don’t get it). As a result, all the plants that bloomed early because of the warm weather not only survived but prospered.

When they cut down a tree 20 or 40 years from now, I expect this year will be a wide ring representing a year of vigorous growth. My wife believes we are seeing strong growth and heavy blooms because of last year’s hurricane. She says the massive soaking (20 to 30 inches over four or five days) they received is causing the growth. I think it may be the lack of competition because so many other trees fell down. The survivors are growing better because they get more sun. Either way, the result is the same: lots of flowers for the bees. It’s been a wonderful spring for the honeybees.

Honey Harvest

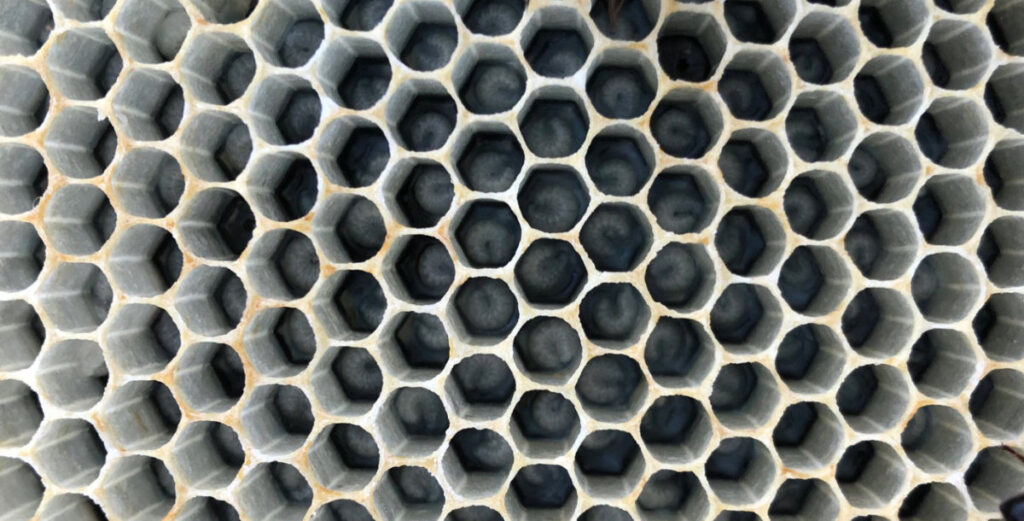

Right now, I have ten hives. Six of them have a total of 14 supers filling up with honey, including the nuc I purchased from Kamon Reynolds, which now has two supers. I consider these six beehives to be my production hives because they are producing honey.

Two of my hives, both from splits I made this year, are doing well enough to have a grown into a second large box or hive body. I am keeping a close eye on them because they may need a super in the near future. I expect these will be producing honey later this month and will be harvested when we pull honey in the late summer.

The two remaining hives are weak. One was a split two months ago and has barely progressed beyond its initial five frames. The other shows a very spotty brood pattern. I am going to feed these two hives sugar water over the next two weeks to see if they strengthen and build comb. If not, I will re-queen them.

Every summer we have lived here, the spring honey harvest has been small and the fall harvest had been larger. I expect this spring’s honey harvest to be a record one. It will be interesting to see if we still get a strong harvest in the fall or if the season is just early. Time will tell.

Raining Queens

I have raised queens before, but I have never grafted them. This may be the year I start.

To graft a queen, you open a hive with a strong queen and use a special grafting tool to scoop a young larva from a single cell on a frame of eggs and young brood. Then you carefully place the larva into a special cup. Next, that cup is placed on a frame. This process is repeated until you have multiple cups on the frame, which is then and inserted into a cell builder or starter hive. The nurse bees in this hive will fill the cups with royal jelly, which is what turns a larva into a queen cell, and starts building the cell.

One key thing is that the cups of larvae must be facing down, which tells the bees in the starter hive that this is a cell destined to raise a queen. Normally, eggs lad in a hive face out, meaning horizontal, not vertical.

After 24 to 48 hours in the cell builder, you move the cells to a finisher hive. As the name implies, this hive “finishes” the cell, including capping it off. After the queen cells are capped, usually on day 7, you can leave them in the finisher or move them into individual nucs where they will hatch. A few days after emerging from their cell, the virgin queens will go on their mating flight. From the time the egg is laid until the queen is born is 16 days. It takes 7 to 10 days for the queen to go on one or more mating flights, return, and start laying.

Selling Queens

You will see commercial or large-scale beekeepers produce frames that hold 30 to 45 queen cells. I plan to graft eight cells on my first try and hope two or three make it through the process. (The failure rate for first-timers is high. Grafting takes practice.) That would allow me to re-queen my week hives and my angry hive that holds aggressive bees. If I have any extras, I can sell them to other beekeepers.

Around here, queen cells sell for $10 or less. Virgin queens sell for $12 to $15. Mated queens—which take more time and effort—sell for $35 to $45.

Queen cells are the least expensive because when someone buys a queen cell, they are taking a risk that the queen will not emerge or might come out with a damaged wing, missing leg, or other issue. When they buy a virgin queen, or one emerges from their cell, is must be mated and then return to its hive. Somewhere between 20 to 30 percent of virgin queens fail to get home. They either get lost, go to the wrong hive, or get eaten while in the wild.

The mated queen is more of a sure thing, which is why they cost more. If you drop a mated queen into your hive, she will lay eggs immediately and should not leave unless she has the urge to swarm the following year.

I don’t see myself raising queens as a side gig. I see myself grafting two or three times a year to fill my own need for new queens. If I can make a few bucks at the same time, all the better.