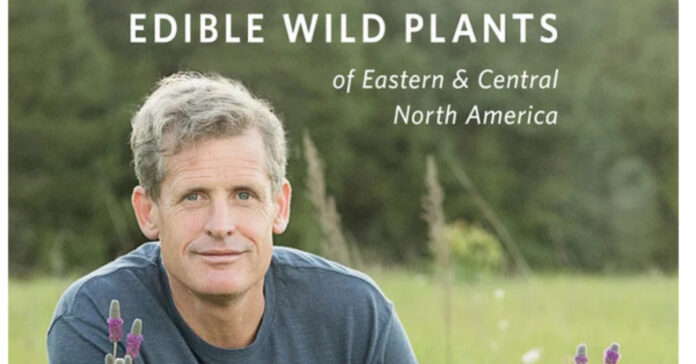

My prepper library is pretty extensive, so I rarely find something worth adding to it. Too many books are simply new ways to say the same old thing or old ideas reframed to fit a new situation. Sam Thayer’s Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants of Eastern and Central North America is an exception and contains reams of new information not available elsewhere, including 320 more species than the Peterson Guide. This book is a worthy addition to my prepper bookshelf. The only problem is that my wife borrowed it, and it may end up on her gardening bookshelf.

The Importance of Foraging for Survival

Before I get into details about the book, let me explain why foraging is important to me and you can determine if it will be important to you. Because we have limited land suitable for tilling, we are limited in how much food we can raise on our homestead. Most of our acreage is on the side of a mountain, meaning it is steep and forested. For us to change that, we would need to bring in some heavy equipment to clear the land and truckloads of dirt to build terraces. I’m not saying this is impossible, but because of the expense, it won’t be happening anytime soon. Realistically, it may never happen.

In an emergency, we could boost our food production, but not to produce sufficient calories to support us all year. That means we will need to hunt, fish and forage to extend the number of years we can stretch our stored food.

In a post-SHTF situation, I expect others will be hunting and fishing, but I don’t think many of them will be foraging. Those that do will probably be focused on some very obvious and recognizable foods, like apples, blackberries, persimmons and maybe black walnuts. Some will know enough to harvest parts of cattails and dandelions. I believe very few will know that they can forage amaranth seeds or eat several parts of the thistle, including immature flower buds which can be peeled and eaten much like artichoke hearts.

In short, owning this book gives you an advantage over other foragers and opens up the possibility of finding more wild food than you ever thought possible.

What Makes this Book Better

I have several books on wild plants, but none of them are as detailed and well organized as this one. For example, I have enjoyed several books by Christopher Nyerges, but much of his expertise relates to California, where he lives. I don’t live there and I don’t plan to. Also, Nyerges excellent Guide to Wild Foods and Useful Plants covers 70 plants and 100 photos. Sam Thayer’s Feild Guide covers 700 edible species and includes 2,000 photos.

Most impressive, Thayer has included only foods that he has eaten. He isn’t repeating old lore attributed to early colonials or trappers unless he has tested it himself. In fact, the book contains a list of “plants not included” that lists plants reported to be edible by other sources but he has been unable to find because they are rare, they aren’t appetizing and don’t taste very good, or they require significant processing to render them safe for consumption.

The book also contains a section on poisonous plants or plants that you might confuse with similar looking edible plants. Some of these, like the common buckthorn (rhamnus carthatica), have appealing berries and look like they should be edible. Others are so dangerous multiple people have died from eating them. So not only does this book tell you what you can eat, it details what you must avoid.

Plant Identification

You don’t have to be a botanist to use this book, but you should know some of their terms. Thankfully, there is a detailed glossary to help you understand the difference between a bristle-tipped leaf and a claw-tipped leaf. (The section on leaves alone will help make you an expert in plant identification.)

Here’s a scenario: You find a plant growing prolifically on the banks of a creek near your retreat. You have no idea what it is, but there’s so much of it, you hope it is edible. So, you take a closer look and decide it is herbaceous and not woody. You look at the leaves and see that it does not have basal leaves (meaning the leaves are not at the base of the plant) and it is not a vine. It has simple leaves that are toothed, not lobed. That’s enough to tell you to turn to page 600 and continue your search there. You quickly realize you are looking at jewelweed. You confirm this by reviewing the description. Yes, the midvein is purple and slightly depressed, and the petioles are hairless.

Only once you have compared all the details plus the pictures can you be sure it is jewelweed. Then you can see what parts of it are edible and when to harvest them. For example, it’s too late to eat the young leaves of new seedlings, but you can eat ripe seeds in the late summer. You note this and decide to come back in August to check on them. You may only get a few handfuls of seeds, but they will make a nutritious addition to your oatmeal. Plus, you now know what jewelweed looks like. You may come across more of as you explore your surroundings.

Not for the Faint of Heart

My wife is a master gardener and has attended classes on plant identification. She already knew what a petiole was (it is the stalk that attaches the leaves to the primary stem) and the other botany terms. I’ve seen her tell one plant from another because one has teeth on the leaves and the other is smooth. She likes nothing more than finding a new plant and using a host of resources to identify it, so this book is right down her alley. For the rest of us, it will take some upfront work and possibly some time before we can look at a plant and say, “Hmm, that’s an interesting herbaceous vine. I wonder what it is?” But then again, it’s an educational process yielding useful information. Even if you never need to eat a hairy vetch, it’s nice to know what that plant with the purple blossoms is.

Eating wild plants is also not for the faint of heart because these are often new and unusual foods. Even if you love kale and Swiss chard, you may come across some wild green that, while edible, is less appealing. (I guess it comes down to how hungry you are.) One thing to keep in mind is that foods you forage have far more nutrients than commercial plants harvested on over-farmed, heavily fertilized lands. When you are eating rice, beans, pasta and the occasional can of Spam, some fresh greens, sweet berries, tasty tubers, or crunchy nuts will be a welcome addition from both a nutritional and flavor standpoint. This book will help you reach the point where you can confidently find, harvest, and eat wild plants, especially those that grown on this side of the Rockies.

Rating

Five Pickles

Highly Recommended. A worthy addition to the bookshelf of any prepper, homesteader, bush crafter or anyone else who wants to identify edible plants in the wild to better live off the land.

NOTE: While I had seen references to this book online, I bought it from Books-a-Million using my personal funds. The author or publisher did not provide it to me and I have not been compensated for my review. This review is based on my opinion with some input from my wife, but no third parties influenced it. I read multiple sections of the book and used it to identify several plants, most of which I did not know were edible.

You can look for this book and others by Tom Thayer at your favorite bookseller or on his website, foragersharvest.com