It snowed during a cold snap this past weekend, but the snow melted as temperatures climbed into the 60s. Tiny flowers along the forest floor, which my wife calls “spring ephemerals,” are blooming. I decided it was time to do a deep dive into my beehives. I had heard through the bee grapevine that there had already been swarms in the valley 30 miles away and some 2,200 feet below us. By inspecting my hive, I could take steps to make sure mine would not swarm.

Swarming

For those that do not know what swarming is, here’s a description: When a beehive gets too crowded, the queen will lay some eggs in special cells known as queen cups. These eggs will hatch into new queens rather than worker bees or drones. When the queen cells are capped over, it means a new queen will hatch in just few days. Before the new queen can be born, the old queen and a third to or more of the bees in the hive will leave and look for a new place to live. After the bees abscond from the hive (and yes, that is a technical bee term) they form a cluster or swarm of bees, often hanging on a nearby tree branch or other perch. The bees cluster together to help protect the queen and keep her warm, making what looks like a ball or cylinder of bees.

While the swarm hangs together, scout bees fly around looking for a new place to live, like a hollow tree or an opening in your porch roof or another manmade structure. Smart beekeepers capture the swarms and relocate them to a new hive. Smarter beekeepers, or those with good timing, spot the signs of a swarm in their hive before it happens and split the hive into two or more parts. By creating a split, the beekeeper gets a second hive without buying new bees. Not only is this far easier than trying to capture a swarm of bees hanging on a branch fifteen feet above your head, it helps protects his original hive, because a third of the hives die after a split. It also saves the bees that would normally leave, as many swarms do not survive for long in the wild.

The purpose of my inspection was to see if there were any signs if a pending swarm and to consider splitting the hive. During an inspection, if you see capped swarm cells, it is a sign your bees are going to swarm. If you want to stop your hive from swarming, you must split your hive, putting the existing queen in the new split.

Three Hives

When I checked my hives during a warm day in late February, all three had survived over the winter, although one was weak. Unfortunately, the weak hive had since died. The hive was full of honey and nectar, so they had not starved. It appears that they had frozen during one of those aforementioned cold snaps. There was a small cluster of bees still on the frame, but no brood. My guess is the queen had stopped laying or died at some point and the hive could not produce any new bees or a queen, although there were a few attempts at queen cups on the frames.

The other two hives had come through with flying colors and are doing quite well.

Hive 1 Looks Good

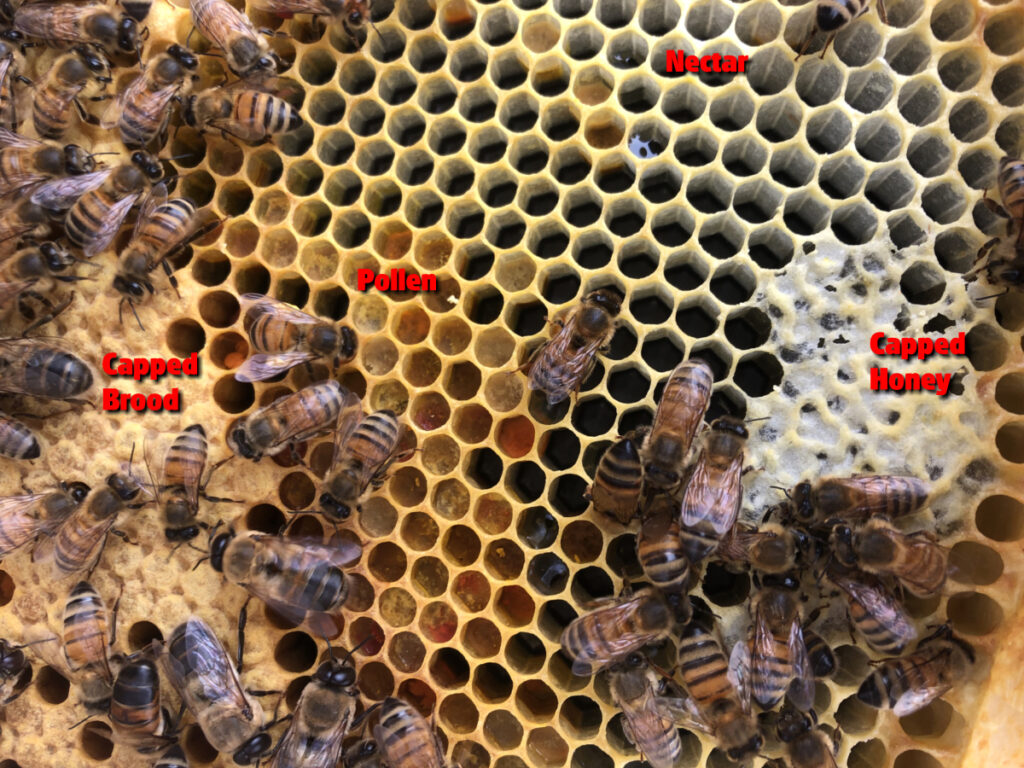

When I opened Hive 1, I immediately saw six or seven rows of bees in the top box, which has ten frames. There were six frames of eggs, larvae, and capped brood, meaning that queen was still doing her job. The remaining frames were loaded with honey and some pollen. I tested the hive for Varroa mites and found none.

One frame was a drone frame, which uses larger cells and where the queen usually lays eggs that hatch into drones instead of worker bees. Because drone brood is the preferred place for varroa mites (the bane of bees and beekeepers) to lay their eggs, I scraped off the drone brood and fed it to my chickens. They gobbled up the larvae and undeveloped bees like a hungry man at a buffet.

Drones are male bees. They do not contribute to the hive. Their sole job is to mate with any virgin queens. Worker bees are females and, as the name suggests, do all the work from caring for the queen and the eggs, to foraging and protecting the hive. In comparison, drones are freeloaders. They don’t have to do any work, and they die after they impregnate the queen. Since we’re on the topic, the queen mates with multiple drones over the course of several mating flights and then never mates again. If the hive doesn’t swarm, she will probably never leave the hive.

Performing A Reversal

I set the top hive body aside and examined the lower hive body, which was a medium rather than full size. Surprisingly, all ten frames were empty, except for a small amount of nectar. I decided to reverse the boxes, setting what was the top box on the bottom. This was easily done after I cleaned off the bottom board. I reassembled the hive and made sure it was level left-to-right and shimmed it so it was tilted slightly towards the front.

My preference is to use large boxes for the hive bodies and the medium hive boxes as honey supers, so this reversal presented an excellent opportunity to remove the medium box and replace it with a large one. I shifted a frame of capped brood from the lower box to the upper one, added a frame of drawn comb and a frame of food. I then replaced the frames I removed from the lower box with frames that held only foundation.

This accomplished several things: First, it gave the queen extra room in the box where she has been spending all her time. This should stifle, or at least delay, any desire the hive has to swarm. Second, it gives the bees room to expand upward. The frame of brood will attract the bees from below. When the brood hatches, the pheromones that are released will draw the queen upward to lay new eggs. Once there, she will get used to laying eggs in both boxes. Third, this new box provides additional room for all the bees that the six frames of brood that will hatch in the next days and weeks. If each frame was only half full, that’s and still 20,000 or so new bees.

Hive 2 is Packed with Bees

The second hive was packed with bees. I had left a honey super on the hive last winter to ensure the bees had plenty of food. When I opened the hive, both the medium super and the large hive body below it had multiple frames of brood. This is the hive that went queenless late last summer, so the new queen is going full steam ahead. So far, it looks like she is doing a great job.

I expected the bottom box, which was also a large hive body, to be relatively empty, but there was a small amount of brood and frames full of pollen and nectar. There was also some capped honey. This hive has so many bees, it would be great to split, but I don’t have a queen and I don’t want to waste the time it takes the bees to grow a new queen in a walk-away split. I am helping a local commercial beekeeper on Wednesday and a fellow backyard beekeeper on Friday. I’ll see if any of them have an extra queen or queen cells I can buy. If so, I’ll split the hive and add the new queen. If not, I guess I’ll have to reconsider and do a split in which the bees make their own queen.

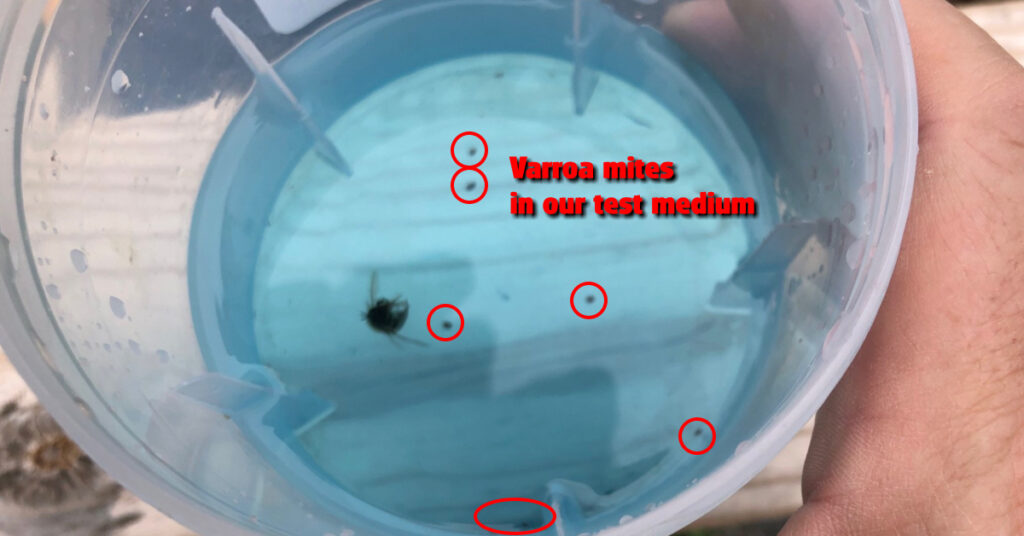

The only downside of this hive is that when I tested it, I found 8 varroa mites in a sample of 300 bees. That’s too high a number for this time of year, so I treated the hive with Formic Pro. Because varroa spread from one hive to the next due to drift, I then had to re-open and treat the first hive, even though it didn’t have any varroa. I added a set of plastic drone foundation to the second hive as part of an integrated pest management program. More fun food for the chickens and hopefully less varroa in the bee hive.

Ready for the Spring Honey Season

Both hives look to be in good shape, especially considering the cold weather we experience through March and into April. I believe this is because I have been feeding it both sugar water and pollen patties since late February. The bees are bringing in enough pollen right now that I don’t need to feed more, but they could still use some sugar water. You are not supposed to feed your bees inside the hive when treating them with Formic Pro. I’ll have to do some open feeding until the local apple trees bloom.

I have seen bees visiting a field of violets and a neighbor’s cherry tree, but the spring honey season won’t reach high gear until the tulip poplars bloom, and that is still weeks away.

Really enjoy your articles on Bees and Chickens. Also, I’m glad that I have adjusted to the new format. In reality, it’s really not that new, just a lot more info. Thanks for your efforts.

Thank you! As we head into spring, I can promise more articles on both.

Comments are closed.