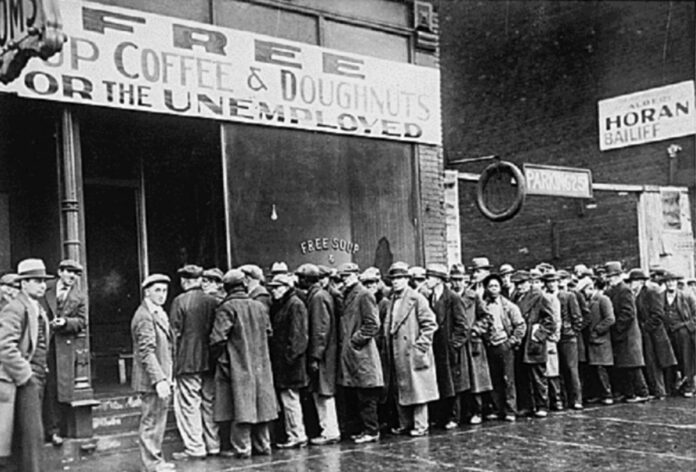

The Great Depression was a bad time for the country. Jobs disappeared, mortgages were called, families lost their homes, and children got sick and died because of a lack of food. The Roaring Twenties, with their wealth and excess, were forgotten as crop failures and dust bowls swept the county. Fortunes were lost and lives were destroyed. Unemployment in some areas reached 40 percent. Poverty became pervasive. It changed the face of America.

My parents were children during the Great Depression, but it affected them. They learned lessons that lasted decades.

For example, in the 1960s, my parents had bank accounts, but they didn’t really trust the banks. They kept cash hidden in the house. One stash I knew about was a metal Band-Aid box, which they kept in our medicine cabinet. (Hiding it in plain sight, I guess.) They would raid it before going out to dinner or if we took a trip for the weekend. I don’t recall them using credit cards back then, but they used traveler’s checks when we went on vacation.

My father eventually outgrew his distrust of banks. When I took over his finances because of to his advancing age, he had checking accounts with seven different banks. I don’t know why. I winnowed him down to three accounts at two banks.

Stashing Cash

My mother’s father was sent to San Diego with the Navy in WWII and she spent several years of her childhood worried that Japanese bombers would strike the mainland. The threat was genuine enough that they had blackout curtains on their windows. She would get over her fear of being bombarded, but the Great Depression left a lasting mark. When she died, we found more than $5,000 in cash tucked away in various hiding places around the house. (We can only hope we found it all.) It took my father several years to spend it.

When my mother went to the grocery store in the 1970s, she would pay by check. The store had a policy where you could write the check for $20 more than was due. She would do this every time, pocketing the $20. Do that for 50 weeks, and you’d have $1,000, which was a small fortune in the early 1970s. I expect that was the source of her early stash of cash. Years later, if she got an insurance check or dividend check in the mail, she would often cash it instead of depositing it.

The Value of a Chicken

My mother would tell the story of how in the 1930s they ran over someone’s chicken, which had run into the road. Knowing that chickens were valuable, her father approached the house and offered to pay for the dead bird. The family refused to accept any cash, but they kept the dead chicken. I am sure it made a good dinner or two.

She felt sorry for a boy she went to school with because his family did not have a radio. If they wanted to hear Roosevelt’s fireside chat or the Lone Ranger, they had to go sit in the car.

She had an older uncle or great uncle who was considered rich because he owned a car dealership. A car dealership back in the 1940s was probably on an unpaved lot and 10 to 20 cars, but it still represented wealth. Someone tried to break into his house one night. He heard them trying the door knobs, looking for an unlocked one. He grabbed his gun and waited. When the burglar tried the kitchen door, her uncle shot right through the door, aiming a few inches above the door knob. The burglar fled, but the police later caught up to him because he’d been shot in the arm. Everyone felt justice had been served. So had a warning; word spread and no one tried to break into their house again.

I remember he had a large revolver sitting on the living room mantel. I was never allowed to touch the gun and had to admire it from afar. Years later, when I got into guns, I would recognize that it was a Colt single action revolver. I often wondered what became of that gun, but it did not get passed down our side of the family.

Gardening

My paternal grandparents had a 50-acre farm. It started as a one-room house and my grandfather added on to it over the years, a room or two at a time. By the time I came along, they leased most of the acreage to a neighboring farmer who grew corn on it for silage. It seemed huge to me. The farm had a wooded section where we would gather firewood and a large row garden at least 100 feet long and churned out many pounds of vegetables. Every time we would visit, we would leave with armloads of vegetables and firewood piled into the back of the family station wagon. My grandmother canned vegetables for the winter, and we would eat string beans on every visit. She also canned pickled watermelon rinds, which are better than they sound.

Farmers and people with acreage generally fared better during the depression than those in the city. They may not have had much money or new shoes, but the had food. Having a large, productive garden was a trait my grandfather carried with him after living through the Great Depression. He worked for an electric utility as a lineman and because they were electrifying American, he usually had work. Still, when I graduated from college in the 1980s and got my first job, I made $16,000 per year. My father said to me, “That’s more than your grandfather made when he retired.”

My paternal grandfather was never wealthy, but neither was he poor. He held stock in the electric utility, probably through an employee stock purchase program, that my father still owns today, although the name changes with every acquisition. I expect our family has collected a fair amount of dividends over the past 80 years. Maybe even more than the old man made in his lifetime.

Family Lessons

If I had to draw some lessons on how to live through the Great Depression based on this brief family history, I guess it would boil down to this:

- Don’t trust financial institutions

- Keep some cash at home

- Have a garden and preserve food

- Chickens are valuable

- Don’t be afraid to use a gun in self defense

- Even during a depression, some blue-collar jobs will exist

- There is value in the buy and hold investment strategy

You could do worse than abiding by those rules, whether you are prepping for a financial collapse or some other disaster.

The Great Depression

My parents were not the only ones who carried lessons from the Great Depression with them, but the further back that time grows, the fewer people heed them. Now we may be doomed to repeat those mistakes. Midwest droughts could lead to another dust bowl, or at least food shortages. The stock market could crash again.

The Dow Jones Index reached a high of 381 in September 1928. Then it lost 13 percent in one day. In 1932, it hit its low of 41.22, a decrease of 89 percent. To put that in perspective, the Dow closed Friday at 34,407.6. If it were to lose 89 percent, it would sink to less than 3,785. Don’t think this isn’t possible. Individual stocks crash and burn every day.

Just keep in mind: don’t trust the banks, have some cash on hand, diversify your investments, plant a garden, raise chickens, and do whatever you can to keep an income stream coming in.