I cannot count how many times people have said to me “moving water doesn’t freeze.” It seems to be a mantra around here where many people rely on gravity fed water systems. Unfortunately, our spring-fed gravity-flow water system continues to prove that this is not the case.

After my post on February 6 saying that we still had water, my friend Karl and I climbed up the mountain and found TWO different places where the pipe had not only frozen but had split due to ice pressure and was leaking. (I guess I spoke too soon.) One of the leaks was a rather robust squirt. The other was a slower seep, but it was downhill from the fist leak, so it probably wasn’t getting the full force of the water. At each place, we cut an eight or ten inch section out of the pipe to eliminate the hole and the surrounding weakness and bulging caused by the freezing. Then we inserted a new coupling.

By the time we got up there to do the repairs, it was in the low 40s for at least the third day in a row, but a surprising amount of ice remained in the pipe. We ended up disconnecting one of the lowest connections and letting the ice out. We do this by holding the pipe up and letting the water build up a good head. Then when we put the pipe back down, the water pressure blasts out a bunch of ice. By repeating this enough, and doing it when it is above freezing, the ice eventually all comes out like an ice gusher.

Friendly Input and Advice

Having used up all the extra couplings and hose clamps, we stopped to the local hardware store to restock and mentioned my problem to some locals.

“Let your faucet trip, that always works for me because moving water doesn’t freezes” say the cashier, who is one of the nicest people you’ll ever meet.

One of the fellows there says he has an above-ground pipe on his spring-fed gravity-flow water system and it has never frozen because—you guessed it—moving water doesn’t freeze. I express doubt and he repeats the mountain mantra: Moving water doesn’t freeze.

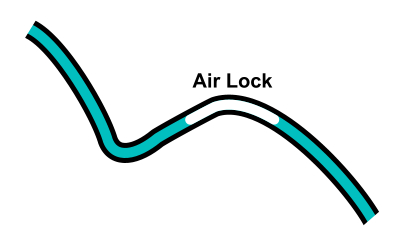

This precipitates a lengthy discussion about why our piping is freezing. We describe the system, its length, its tank and the overflow. He agrees this is a pretty standard set up. We agree that the overflow should keep the water running. The he suggests that we may be getting an air lock or vapor lock and this is causing the water to stop running and then it freezes.

He recommends that we insert some three-foot stand pipes that will allow excess air caught in the pipe to escape.

At the time, I have no idea if this is a possibility, but I do know that there is a reason drain pipes in your house have a vent, so it sounds entirely plausible. We buy some three-way couplings and about 10 feet of pipe. We also buy a ratchet-type of pipe cutter designed for PVC pipe. Let me tell you, it works like a dream! Highly recommended.

What is an Air Lock

Back at home, I read up on air locks and vapor locks in plumbing. I’ve going to give you the layman’s version, since I am not an expert in plumbing or fluid dynamics. If you want a full description, check out the Wikipedia page and see their image or just do a search on airlocks in gravity-fed water systems.

We all know that air is lighter that water, so when it is in water, air floats to the top. Now imagine that you had a hose that went down a hill, up a hill, and even further down hill again. Any air in the water might accumulate at the high point in the hose because air rises. Over time, an air bubble forms. As the air bubble grows, it gets so large that it stops water behind it. In a normal situation, the water pressure behind the air lock might build until it becomes powerful enough to overcome the buoyancy of the bubble and force the air out of the peak and all the way down the pipe.

In our case, what the knowledgeable fellow at the hardware store is suggesting is that the air bubble in our pipe is causing the water to hold still long enough that it freezes. He may well be correct because as we have been told multiple times, moving water doesn’t freeze.

By installing the stand pipes, we give the air bubble an easy out. It rises out of the vertical section of pipe we will install while the water keeps downhill and into our tank. One critical thing my online research made clear is that to be effective, the stand pipes, or air release vents, have to be at the high points of the pipe’s path where air locks might be occurring.

Installing the Stand Pipes

The next day, we don our gear, pack up our new equipment and hike up the hill. Again.

There is one location near the bottom of the pipe run, close to where the tank is located, that is a high point. Much of the icing has appeared immediately above this section, so we install a pipe there. We cover the top of it with a couple layers of screen and duct tape it in place to keep out bugs and small critters. Then we use ware to attached it to a tree to keep it upright.

We climb up the whole dang hill to the spring, looking for high points that might cause an air lock. Where we find them, we either install a stand pipe or adjust the pipe by setting rocks under it to raise low points or re-routing it slightly to smooth out high and low points.

We end up installing one vent pipe near the top where the pipe dips and climbs a bit. We install a third one in the middle where there was already a splice. I believe the top and bottom stand air vents were probably necessary. I am not convinced the middle one was, but we had the parts and we figure it can’t hurt.

More Neighborly Advice

The next day, we are returning home from an excursion and we see a couple fellows walking up the road, so I pull over and introduce myself as the guy who bought “so-and-so’s” house. We chat, they welcome us to the neighborhood and they ask how things are going. I tell them things have been going great but our spring fed well has frozen two or three different times. The one fellow commiserates about how cold it’s been and tells me he had to fix frozen pipes himself this year. The other fellow tells me to leave my water dripping because moving water doesn’t freeze.

At some point during the conversation, they find out that our supply line is above the ground and they look shocked. “You gotta bury it,” says one. “The deeper the better” agrees the other. We then have a discussion about how we should put the black poly pipe inside a larger pipe to keep the rocks from crushing it and to help prevent damage when we bury it. Great, this is looking like an increasingly expensive proposition.

In any case, my hopes that our new air-pocket release pipes will cure the problem are somewhat crushed. I expect by this time next week, we’ll have had enough cold weather to know for sure whether or not they solve the problem.

Moving Water DOES Freeze

We all know still water freezes at 32 degrees. Contrary to public opinion, moving water can and does freeze. For proof, look at an icicle and realize that water has dripped down (moved) and then frozen to form the icicle.

It is more accurate to say that fast-moving water will not freeze at 32 degrees. The action of the water flowing carries an energy of its own that prevents the water molecules from freezing to each other because they are constantly getting mixed up. This is why the stream on our property don’t freeze solid.

The streams do accumulate ice on the sides and where water has splashed onto a rock, however. The problem is that our pipe does not contain as much water as a stream, and the sides of the pipe are much closer to each other and easier to block than a stream. We haven’t done any testing, but is certainly possible that the moving water in our pipes would freeze if it (the water, not the ambient air temperature) reached 12 or 15 degrees.

What may work in our favor is that the water is starting out at somewhere around 58 degrees. It has to be very cold indeed for the water to drop to freezing temperatures say while it is moving downhill and a decent pace. If we can keep the water moving by eliminating the air lock, we may indeed have successfully resolved our problem. Time will tell.

Letting Your Faucet Drip

So now that we have established that moving water can freeze if it gets cold enough, let’s address whether it is wise to let your faucet drip on bitterly cold nights. In my opinion, yes, it is, and we have done so on multiple occasions in a number of different houses.

First, the moving water allows the constant introduction of new, warmer water. This alone may be sufficient to keep your pipes from freezing.

Second, I think letting the faucet run slightly may relive pressure on your pipes and keep them from splitting due to ice formation.

So, to clarify: Moving water can freeze under the right conditions. These conditions may take place outside on the side of a mountain but are far less likely to take place inside you house. Letting your faucet run slightly on bitterly cold nights is probably a good idea.