Stagflation, which the U.S. experienced 40 years ago as prices rose while the economy sank, may raise its ugly head again. The numbers are just in, and the U.S. economy grew only 2 percent in the third quarter, not only below expectations, but the slowest growth since the post-COVID recovery started.

Why, you ask, is the economy sinking? Is it COVID, like the mainstream media claims? Is it unemployment?

It’s the supply chain and the vaccine mandate, which exacerbates the supply chain problem by forcing experienced workers out of their jobs, including truck drivers and warehouse workers.

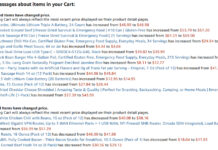

The problem is that we can’t get enough products and parts on the shelf fast enough to fulfill demand. This is constraining spending, which is hurting the economy, which will lead to stagflation. What few good there are will be chased by more and more buyers, driving up the prices and creating inflation. Yet there will be so few goods to sell–cars, toys, cosmetics, appliances, apparel and so forth–that retail sales will be down, which will hurt companies, which will lower earnings and lead to fewer jobs. It’s a slow collapse that was a long time coming. The COVID collapse of our economy and the shutdown of most businesses kicked it off.

The supply chain collapse is much worse than the average consumer believes. Talk to an industry expert and they will tell you it will not be fixed soon and shipping products may get even more expensive. To make matters worse, items that sit on boats for months longer than expected often arrive moldy, rusty, or otherwise damaged by the moisture and corrosive salt air.

The Supply Chain

It’s called the supply “chain” because of the many interconnected links between the manufacturer and the end user. Here are the key those links for a pair of shoes made in Vietnam (or anywhere else in Asia) and sold in your local store:

- The shoes have to be manufactured, go through QC, get hang tags, and put in a box

- All the shoe boxes for that order get loaded into a container at the factory

- Truck carry the container to the port

- Containers are stored at the port until the ship that carries them docks

- The containers are loaded onto the ship

- Once loaded, the ship sails across the ocean

- After it arrives at a U.S. port, it waits, often for weeks, until a slot at the port opens

- Then the boat docks and unloading commences. This process is taking at least twice as long as usual because of the high volume and lack of storage space for incoming containers

- Unloaded containers are stored at the port or in a nearby warehouse until customs clears them.

- Eventually, the container of shoes makes its way to the manufacturer’s distribution warehouse, either by truck or a combination of train and truck

- At the receiving warehouse, they unpacked the containers

- The shoes are checked to make sure they didn’t mold during their excess time in transit and are shelved

- After new inventory is entered into the computer, the computer spits out any open orders for stores that want those shoes.

- A picker is given a pick list with SKUs, quantities and location and goes through the warehouse and assembles the order

- The order is checked and packed

- The order is shipped. Sometimes via UPS or Fedex, but larger orders are palletised and shipped by truck.

Sixteen Links

That’s sixteen links in the supply chain for a shoe to get to your store. The sixteen steps include four to six trucks, possibly more. It includes a boat and potentially a train. At each stop, the shoes have to be handled, usually in bulk but eventually individually. That takes people, which are often in short supply these days.

Those sixteen stops do not include the sourcing of raw materials, from polyurethane and elastomers to high-tech fabrics and shoe laces. That also does not include the supply chain to manufacture and print the shoe boxes and the large corrugated boxes than hold six to twelve pairs of shoes.

A shortage of any raw material holds up the entire supply chain. The lack of shoe laces, eyelets, or the tissue paper for the inside of the box can halt production, leaving an order unfilled.

If those shoes were made in America, and very few are, they could go from the production line to the warehouse, get entered into inventory and used to fulfill orders right away, eliminating more than half those links in the chain and all but one truck.

Transportation Bottlenecks

The big issue slowing down the supply chain is a lack of transportation and storage space. Truck drivers and the chassis, the wheels under a container, are both in short supply. This makes getting containers out of the sports take longer than normal. That results in a lack of storage space as they offload containers from ships, so the turnaround time slows. It also means fewer empty containers that are available to be loaded and returned to Asia for re-use.

The lack of truckers also contributes to slowdowns at rail heads as it takes longer to unload trains because there is nowhere to put the containers when they come off the rail car.

I’ve been told that the problem of too few truck drivers has been obvious to industry observers for a few years, in part because truck drivers are aging out and not very many younger guys are signing up for the life of a long-haul trucker. COVID-19 made the problem worse and sped up the decline, with the loss of 88,000 trucking jobs in April 2020. Who knows how many of those drivers retired or took jobs in other industries instead of returning to trucking when the shutdown lifted?

Just like the government’s promise to eliminate fossil fuels by 2050 means few oil companies want to invest in new production, the promise of automated, driverless trucks means fewer people want to get their CDL. Why invest time and energy in a career where you may be replaced by AI in 10 years?

It doesn’t look like the truck driver shortage is going to be resolved soon.

Critical Parts Shortages

We’ve probably all heard the old saw that ends, “For want of a nail the kingdom was lost.” These days, you could say, for want of a semiconductor, the sale was lost. All over the world, major car manufacturers cannot produce their cars because of a shortage of the chips that make our modern mechanical marvels function. Sometimes, like in the case of chips that are used for wireless phone charging, they can leave that feature out and still produce the car, but many applications (and their chips) are mission critical.

Sales of the Ford F-150 pickup truck, the most popular vehicle in the country, dropped about 30 percent in June because Ford lacked the semiconductors to finish them. As a result, tens of thousands of unfinished trucks sat in lots waiting for chips so Ford could ship them off to dealers.

It’s not just cars. Anything with a digital interface, as opposed to the old analog knobs and dials, uses microchips. It also goes beyond chips. The supply chain problems hurts production of anything that counts on parts made overseas. Repairs are also taking longer, which takes vehicles and machinery out of production. That lack of production means less product to sell, which means less money is spent on goods, which is a critical part of the GDP.

Inflation Hurts Consumer Spending

According to the government, the average household spends about 25 percent of their budget on discretionary spending. That category includes things like eating dinner out, going on vacation, attending concerts, buying alcohol and tobacco products, on their hobbies and sports, and buying consumer electronics.

As the price of essentials like gasoline and food continue to rise, there is less money in the budget for discretionary spending. As their pocket books get pinched and that paycheck gets eaten up faster and faster, consumers will spend less on discretionary items. They will also change their shopping habits at the grocery store, meaning they may eat more hotdogs and less steak. People also cut back on services, getting their haircut less often, painting a room themselves instead of hiring a painter, etc. That hurts small business as well as consumer spending, which contributes 70 percent to the GDP. If consumers spend five percent less, the GDP will drop 3.5 percent.

It’s pretty easy to see how rising inflation could quickly result in a recession.

All that reduced spending trickles down to fewer jobs. Already there are fewer car salesmen because there are fewer cars. When people cut back on vacation, there will be fewer airline tickets purchased and hotel rooms booked, which will also mean layoffs. That’s just going to make the recession worse.

How to Prepare for Stagflation

Many of the things we’ve covered in how to prepare for inflation or hyperinflation apply to stagflation. In fact, if you think of stagflation as inflation with job losses and less work for the self-employed.

As we have said before, you need to have a way to feed your family. You need to be able to produce food or goods for your own use, to use in barter for items you need, or to sell. You also need to identify those areas where you can gut back spending and start cutting back now. Use your savings to stockpile food and enhance your preps before prices rise any further. Consider getting a second job or a side gig so that you still have a source of income if you get laid off.