We are lucky enough to live on our prepper property full time, but I was a prepper for at least 25 years before we could leave the city and move to our isolated mountain. Before that, we had a retreat, meaning somewhere we could go in an emergency.

Give the threat of nuclear war, economic collapse, food shortages, civil unrest, etc., I thought it would be a good time to talk about how you can get or find your own retreat. The need to find a possible retreat may never have been greater.

Before you say, “I can’t afford to buy a retreat,” read on. The good news is that you don’t have to buy a retreat. There are often places you can go for no money at all. Let’s look at the different kinds of retreats, including those that are free.

Temporary Retreats

The first retreat is what I will call the temporary retreat. This is a place you can go when a hurricane, forest fire, chemical spill, nuclear plant melt-down or any other regional emergency affects you, but not those 100 miles away. In most cases, this could be a friend or family member who will take you in for a few days. You get to be the awkward house guest until the flood waters recede, the all-clear is given, or the emergency is over.

For example, if you live on a South Carolina barrier island, it’s a good idea to have friends well inland.

This is one example of a free retreat, where you don’t have to buy it up front or pay rent for it. You may have to reciprocate one day, or take your hosts out to dinner while you are there and send them a nice thank-you gift afterwards, but it will not cost you as much as owning your own retreat.

In most cases, this is not where you want to go in the event of a nuclear war or a societal collapse. It is not necessarily rural, it is simply far enough from your home that whatever localized problem you face does not reach that far. It’s a good first step.

Mobile Retreats

A mobile retreat is an RV or a camper. Again, these are best in a short-term or regional emergency. You might even combine your mobile retreat and your temporary retreat, so you show up at your temporary retreat with your camper. That saves your hosts from having to find the spare towels or complain about your snoring.

The biggest advantage of a mobile retreat is that you can go almost anywhere and carry quite a bit of stuff with you. You are also pretty well self-contained, can cook food, stay warm and dry, and have many of the comforts of home, at least as long as the fuel holds out. If you can find an open spot at a campground that offers hookups, you’ll have water and electricity and maybe even cable TV.

Is your mobile retreat free? No, it is not. It can, in fact, be quite expensive. However, it can also be dual purpose. I would not recommend buying an RV or camper just to use for bugging out. If you enjoy that kind of camping, then having a fully equipped bug out vehicle is just another excuse to justify the purchase of your camper.

Can you throw your tent in the back of your SUV and consider that a mobile retreat? Yes, but it is not optimal. You won’t be able to carry as much gear and you will have to pack each time you go. Many RVers keep the RV well stocked with tools and equipment, but there is no reason you cannot have some pre-packed “grab and go” boxes in addition to your bug out bags.

If you opt for tent camping, it opens up remote road locations your RV will never reach, including national parks.

Permanent Retreats

A permanent retreat is a retreat you own or you have a good enough relationship with the owners that you are invited to stay there when the SHTF (another example of a free retreat). This could be a farm, homestead or other rural home owned by a close relative, or it could be a prepper retreat owned by a fellow prepper.

Because your permanent retreat is for a global disaster, rather than just a hurricane or other local event, it should not be in a city. Ideally, it is in a rural area, off the beaten track, with surface water, trees to harvest for firewood, and room to raise food. There can, however, be some advantages to being in a village or small town, including building good relationships with locals to provide mutual support.

One of the best benefits of a permanent retreat over a temporary one is that you can pre-position supplies there. When we had a permanent retreat, we stashed clothing, #10 cans and 5-gallon pails of food. I also had guns and ammo there, including an AR-15 and an old .22. For a complete list, check out this post: Clearing Out our Survival Retreat and a Look at What We Stored There. That should give you an idea of the advantages offered by pre-positioning things at a permanent retreat.

Many preppers who live in rural areas, and my wife and I are in this category, cannot defend the place by ourselves. In a post-SHTF event, we need other people. In our case, those other people are our adult children and their families, plus another family and their adult children. (Our house is their retreat.) You want your permanent hosts to look forward to your arrival when the SHTF, as we do.

Buying Your Own Retreat

I traditionally have not recommended buying your own retreat until you are well along your prepper journey and have covered many of the basics. Given the last two years, the increase of work-at-home jobs, and what I can only consider to be the deterioration of the global stability, I can’t blame you if you want to run right out and buy a retreat or move to your prepper property. So, how to go about it?

Here are three things you can do, in order of cheapest to most expensive:

- Buy land and improve it as time and money allow

- Purchase a run-down place and improve it

- Buy a move-in ready retreat, and move into it

Buying Raw Land

We considered buying land in Montana, building a large steel building as a barn or shop, and putting a small apartment in it. Then we could take our time to build a full-time residence.

One advantage of this approach is that we could spread the cost of building out over several years. We could bring electric in, install a septic, and then stay in the shop on our occasional visits. In a worst-case scenario, we could bug out there and have many of the basics we would need.

Alternatively, you could buy raw land, put in a road, and park your RV or camper there, either permanently or when you bug out. You could also have a contractor install an ocean-going container there and use it for storage.

Whether you improve your land is up to you and your wallet. Some people have built underground bunkers on otherwise empty land. That’s not a bad idea if you expect nuclear war, but it is a costly one. Even if you never drive a nail into a board, having a road built, knowing where the water is, and keeping any cleared areas from growing up will be worth your while if you ever retreat there.

Buy a “Needs Work” House

When looking for property, we saw many small, old houses that needed work. Sometimes, major repairs. So why would you want to buy a headache? So you can start off with a functional retreat at a lower cost. Unlike buying raw land, an old, out-of-style home should have a septic system, a well or other water source, electric service, and a roof that hopefully does not leak. That saves you all kinds of investment, even if you have to make repairs.

If you are handy and enjoy doing the work yourself, this can be a viable option. I am familiar with someone who bought 5-acres that had an old 1-room cabin on it. They lived in the cabin and built a 1,600 square foot “addition” onto it in two stages.

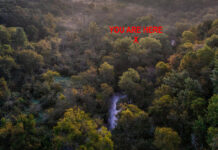

I would also include in this category hunting camps and vacation cabins, small shelters that may be snug but have only one or two rooms. These may be very isolated, may be accessible only by boat or a 4-wheeler but not by a car or pick up. Poor access might be a deficit if you are planning to raise your family there and telecommute, but they can be advantages after the SHTF. The “golden horde” fleeing the cities is unlikely to swarm a small cabin that has no address or driveway, is off the grid, and requires special equipment to access.

If you are in the mountains or a very rural area, you may find a house with outdated electrical service, a septic system that has not been cleaned out for years and has inferior pipes. The roof might be rusty tin and be under-insulated. You could unknowingly sign up for a decade of renovations, but you will also have somewhere to go when the SHTF.

Buy a Move-in Ready Retreat

When we bought our house, the former owner was a hunter, not a prepper; it just happened that the house had many things that made it suitable for a prepper. For example, the house has a wood stove and a fireplace insert for heat and a gravity fed spring water system that provides running water. What it lacked was enough flat pasture to allow us to raise livestock. By choosing to live halfway up a mountain, we traded away the pasture we wanted, but we gained seclusion and the inaccessibility of a dirt road that requires four-wheel-drive parts of the year. As a result, we raise chickens, not goats, pigs, or cows.

That’s an important lesson: No house is the perfect retreat. Even if the past owner was a prepper, he probably did some things differently than you would have done them. Just accept that you will have to compromise. If you can’t make that leap, then go back to option one, buy raw land, and build your own house exactly how you think you want it.

Is a Move-in-Ready Retreat Necessary?

I do not believe you need to buy a retreat you can move into the day after closing, but it does make the transition easier. If you are planning to sell your old house and relocate, which you may have to do to afford a move-in ready retreat, having a house where everything works and there are not any unexpected surprises is a blessing during this hectic period of your life.

Even if you don’t move into your retreat, you should spend time there. I would recommend visiting at least one long weekend a month so you can get to know what it is like in every season. You should also walk the land and general area to get to know it, and introduce yourselves to the neighbors. Try not to be stand-offish or rude, as these people could make or break you in a TEOTWAWKI situation. You want to build a relationship, not shut them down before it can get started. For example, if the neighbor with whom you share a fence line asks for permission to hunt on your land, give it to him. That will win you one fan, and he may look out for your property while you are absent.

One advantage of owning your own retreat is you can do whatever you want to it. You can put up cameras, string barbed wire, cut down trees to give you a better line of fire, and no one can stop you. If you put up some solar panels or a windmill, the neighbors might think it’s an eyesore, but if you have picked a place with no covenants or HOA, they can’t do much about it. (The best bets is to pick a place out of sight of the neighbors.)

When to Retreat

Obviously, we liked the idea of moving to a prepper-centric property, and we made certain sacrifices to do so. If you don’t live at your retreat, the most important decision you can make is when to bug out. I’ve made this point before, but it is worth repeating: beat the crowd and bug out early.

Here are some related articles that may be of interest: